Flames are a common hazard in many industries. Flames are all around us and they serve purposes from conversion of chemical bond energy to heat, propulsion of rockets, to cooking in our homes. These scenarios are planned for and designed to safely occur. However, there are many scenarios where flames are not planned for and can cause catastrophic damage.

Fires cause billions of dollars in damage every year. In the United States alone, the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) estimate that in 2022, local fire departments responded to an estimated 1.5 million fires. Those fires caused 3,790 civilian fire deaths and 13,250 reported civilian fire injuries. The property damage caused by these fires was estimated at $18 billion. See the NFPA Site Here for Further Information

Figure 1:Chemical Processing Fire Example Image. Credit: https://

Figure 2:LES visualization credit to Dr. David Lignell: https://

Learning Objectives:

Describe the nature of fires and explosions.

Define the fire triangle and explain how to use it to prevent flammable mixtures.

Characterize the flammability of gases, liquids, and dusts.

Estimate flammability parameters for mixtures.

Fires and Explosions¶

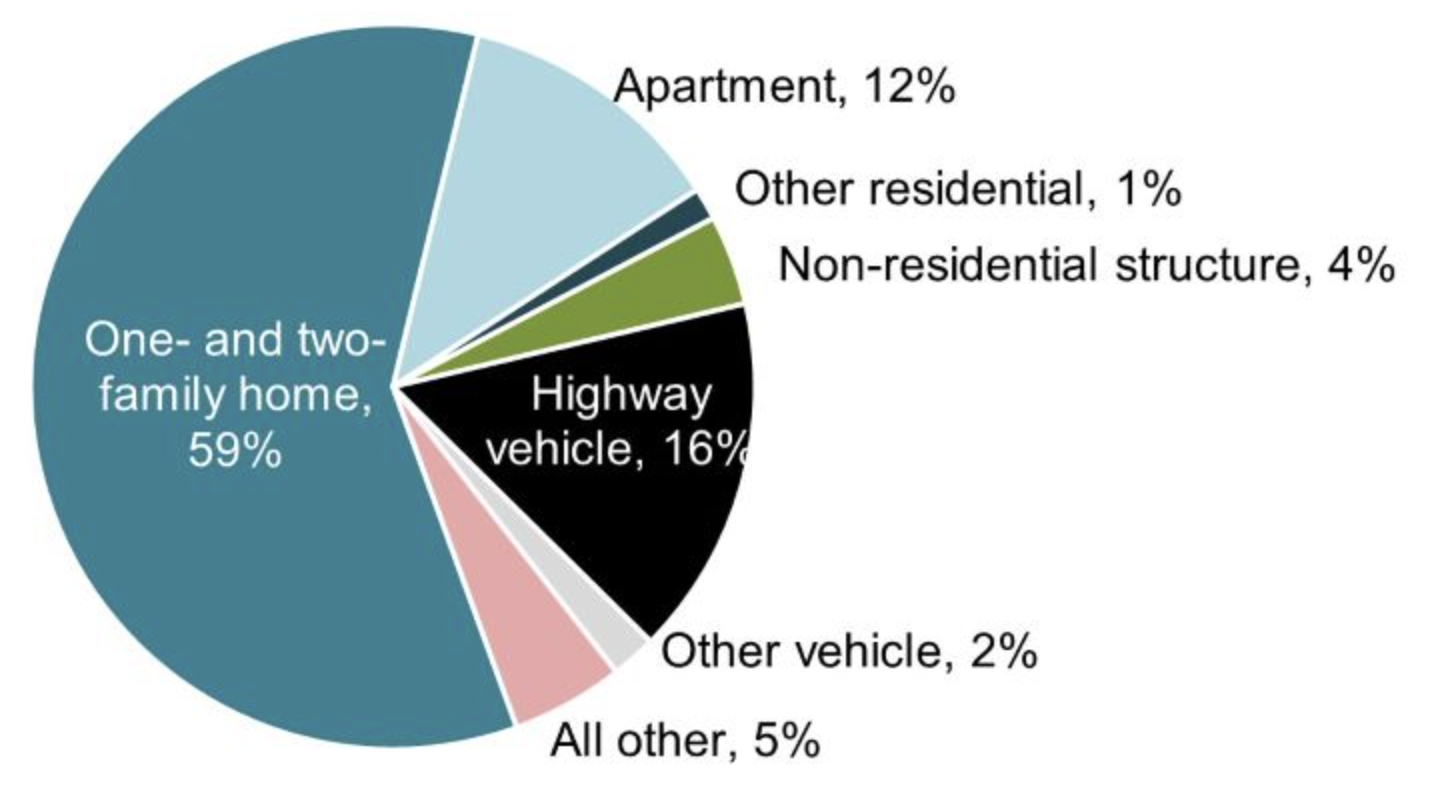

The below pie chart shows the fraction of fires per category for the approximately 4000 people that died in 2022. Notice that the majority of fires are residential fires.

Figure 3:Fire Deaths by Category Pie Chart

Industrial loss of life and property is also due primarily to fires and explosions.

What is a fire?¶

A rapid exothermic reaction. Or in other words, a fuel reacts with an oxidizer once ignited to produce a thermodynamically favored chemical change. Heat, light, and sound can be produced. The heat can be used to sustain the reaction, and the light and sound are often the first signs of a fire.

What is an explosion?¶

An explosion is a rapid release of energy in an uncontrolled manner. This can be due to a rapid exothermic reaction, or a rapid release of pressure. The energy release can be due to a chemical reaction, or a physical change in state.

Hazardous Effects of Fires and Explosions¶

Thermal radiation

Asphyxiation

Toxic gases

Blast waves

Fragmentation

Theses effects can cause damage to property, injury, and loss of life.

How do fires start?¶

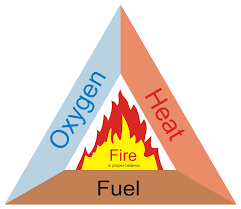

Figure 4:Fire Triangle. Credit to https://

Fires and explosions require a fuel, an oxidizer, and an ignition source. This is known as the fire triangle.

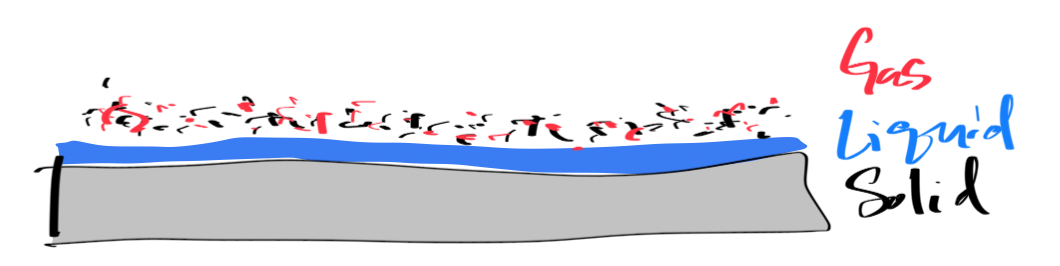

What actually burns?¶

In all but the most unique of circumstances, it is the vapor of a liquid or solid that burns. The vapor or gas mixes with the oxidizer and ignites. The heat from the ignition sustains the reaction.

Figure 5:Surface Melt and Vaporization

How to Prevent Fires and Explosions¶

Ignition sources are plentiful and can be difficult to control. However, the fuel and oxidizer can be controlled. The most common way to prevent fires and explosions is to control the fuel and oxidizer. Often either the concentration of the fuel or the concentration of the oxidizer is controlled to prevent a fire or explosion.

How low or high do the concentrations need to be altered?¶

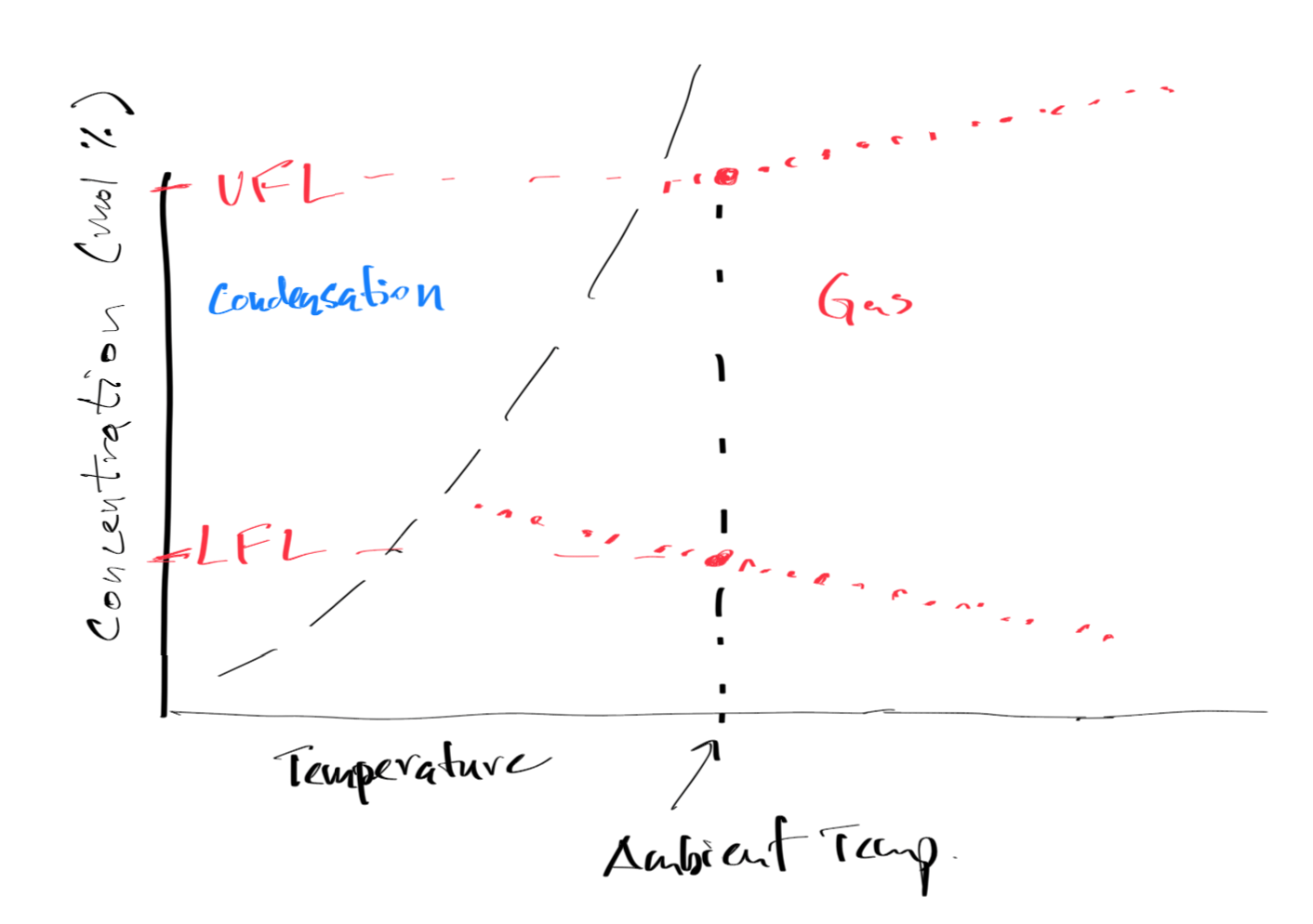

Lower Flammability Limit (LFL)¶

LFL: LFL is the lowest concentration of fuel in air that will support a flame.

LOL: LOL is the lowest concentration of a fuel in pure oxygen that will support a flame.

LOC: Also can define LOC (Limiting Oxygen Concentration) as the lowest concentration of oxygen in air that could result in combustion for a given fuel. This can be defined for oxygen in air or for a different gas.

Units are typically in volume percent (vol%) or equivalently mole percent (mol%).

Upper Flammability Limit (UFL)¶

UFL: UFL is the highest concentration of fuel in air that will support a flame.

UOL: UOL is the highest concentration of a fuel in pure oxygen that will support a flame.

Units are typically in volume percent (vol%) or equivalently mole percent (mol%).

Typical Values for LFL and UFL

| Substance | LFL (vol%) | UFL (vol%) |

|---|---|---|

| Methane | 5 | 15 |

| Propane | 2.1 | 9.5 |

| Hydrogen | 4 | 75 |

| Gasoline | 1.4 | 7.6 |

| Ethanol | 3.3 | 19 |

| Acetylene | 2.5 | 83 |

Typical Values for LOC in Air

| Substance | LOC (vol%) |

|---|---|

| Hydrogen | 5 |

| Methane | 12 |

| Ethane | 11 |

Controlling the temperature¶

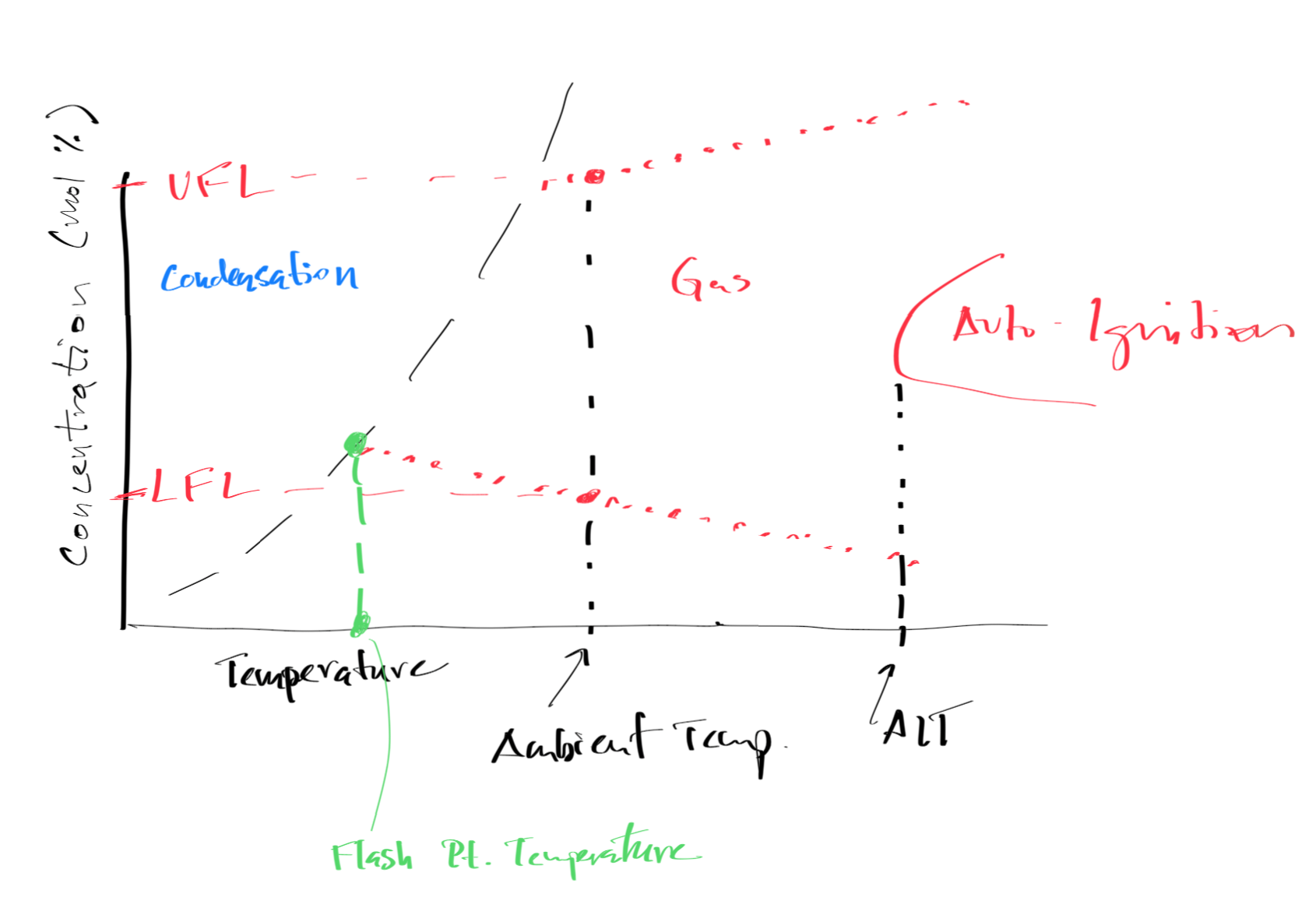

Flash point temperature is the lowest temperature at which a liquid gives off enough vapor to form an ignitable mixture with air near the surface of the liquid.

Typical Flash Points

| Substance | Flash Point (°C) |

|---|---|

| Methane | -188 |

| Propane | -104 |

| Gasoline | -43 |

| Methanol | 11 |

Autoignition temperature is the lowest temperature at which a substance will spontaneously ignite without an external ignition source.

Typical Autoignition Temperatures

| Substance | Autoignition Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|

| Methane | 600 |

| Toluene | 536 |

| Gasoline | 280 |

| Methanol | 463 |

Graphical Image of Flammability Limits, Autoignition Temperatures, and Flash Points¶

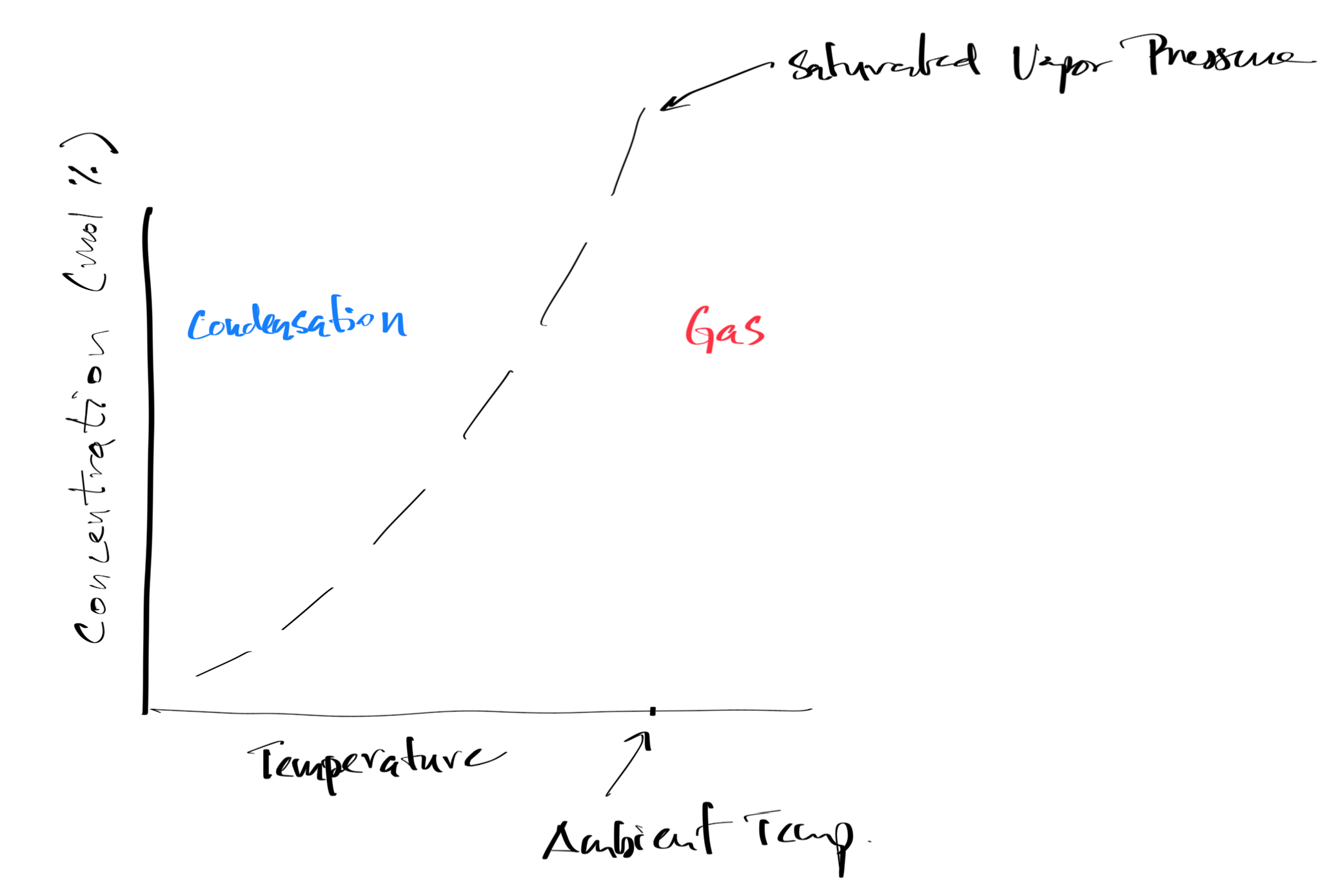

Figure 6:Graphical Image of Vapor Pressure

Figure 7:Graphical Image of LFL and UFL

Figure 8:Graphical Image of Autoignition Temperatures

Figure 9:Graphical Image of Flash Point

Equipment used for experimental determination¶

Flash point¶

Closed cup apparatus

Figure 10:Closed Cup Apparatus Image 1

Figure 11:Closed Cup Apparatus Image 2

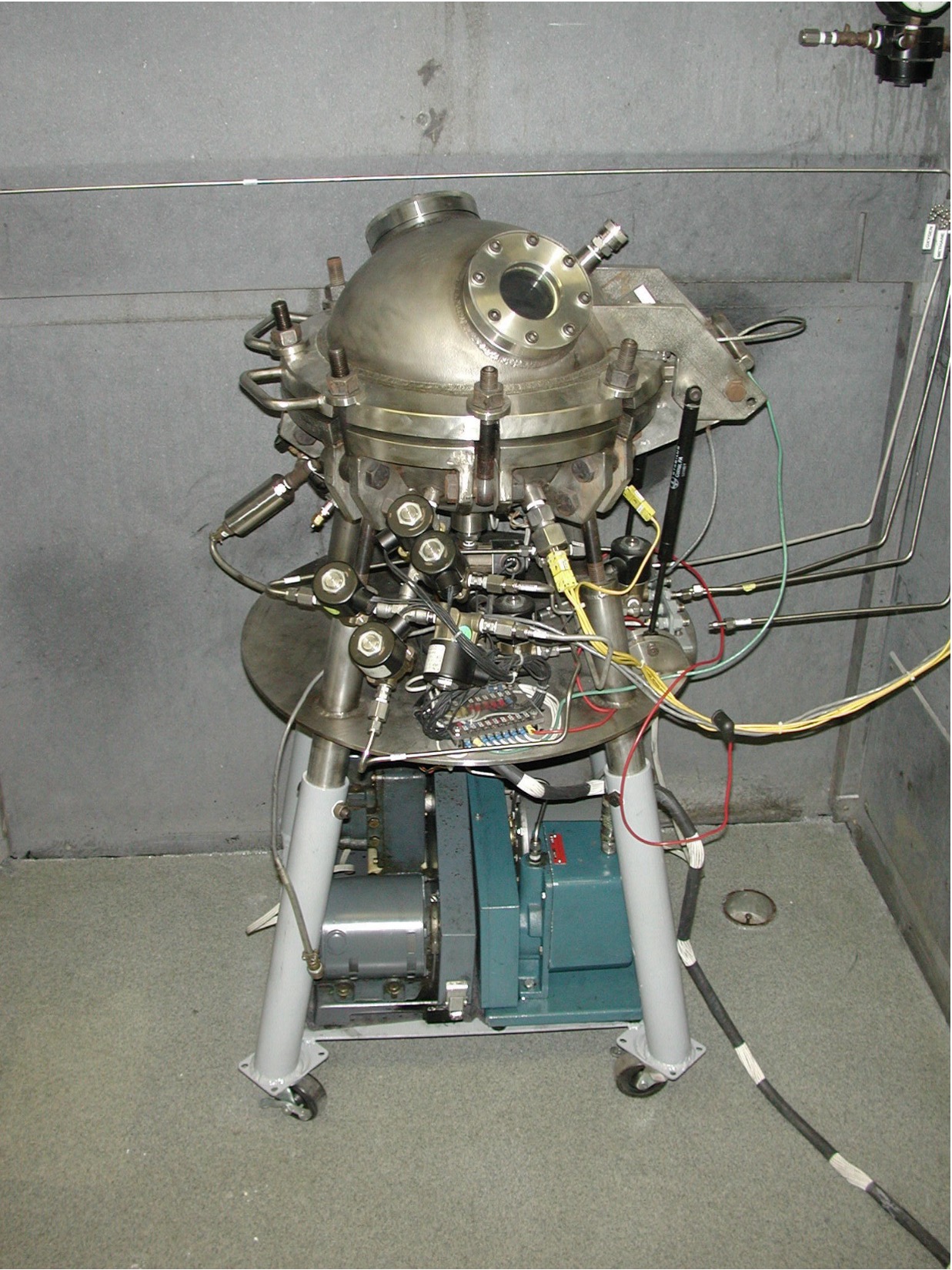

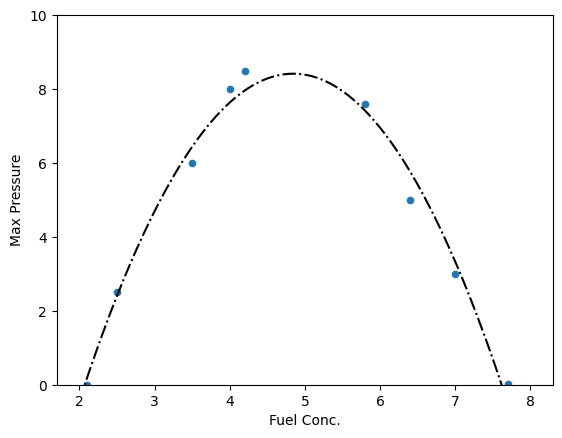

Flammability limits¶

Figure 12:20 Liter Sphere

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pddata = {'Fuel Conc.':[2.1,2.5,3.5,4,4.2,5.8,6.4,7,7.7],'Max Pressure':[0,2.5,6,8,8.5,7.6,5,3,.03]}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)df.plot(x='Fuel Conc.',y='Max Pressure',kind='scatter')

#fit a parabola to the data

p = np.polyfit(df['Fuel Conc.'],df['Max Pressure'],2)

#plot the parabola

x = np.linspace(2,8,100)

y = lambda x: p[0]*x**2 + p[1]*x + p[2]

plt.ylim(0,10)

plt.plot(x,y(x),'k-.')

plt.show()

Empirical Estimation of Flammabilities¶

From Crowl and Louvar (4th edition of Chemical Process Safety, Chapter 6), the following empirical equations can be used to estimate the LFL and UFL for a gas or vapor:

Flash Point

where a,b, and c are constants, and is the normal boiling point of the liquid and T_f is the flash point. See Crowl and Louvar for the constants.

Reaction Stoichiometry

How do you get the stoichiometric concentration for say propane in air?

LFL and UFL: Mixtures

where is the mole fraction of the component and is the LFL of the component. The UFL is calculated similarly.

UOL

where UFL_o is the oxygen concentration at the UFL. 1.87 is a fitting constant.

- Guymon, C. (2025). Foundations of Spiritual and Physical Safety: with Chemical Processes.